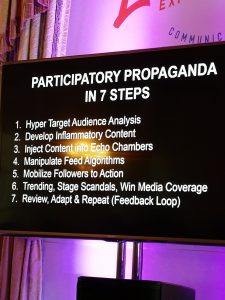

Slide by Alicia Wanless at CPRS’ annual conference, June 2019.

Propaganda is everywhere these days. Even (especially?) at a conference for public relations professionals.

La Generalista, aka Alicia Wanless, was the opening keynote speaker at the recent Canadian Public Relations Society’s (CPRS) “Evolving Expectations” annual conference, held this year in Edmonton, Alberta.

Ms. Wanless, a researcher at King’s College London, is an expert on information and propaganda, areas of study that are crucial to strategic communicators – especially the former as our currencies of trade are information and persuasion. So they are of interest to me, a professional communicator, but why should scientists care? I will get to that shortly.

Slide by Alicia Wanless at CPRS’ annual conference, June 2019. “General Trust In – 49% Media, 46% Government, 49% Business”

Her talk was titled “Armed with Ethics: Winning the Battle Against Information Warfare” and she shared insights gained from over ten years of research and analysis. Ms. Wanless warned us that digital tools and technology have made large-scale persuasion more possible. Here is an example (not hers) with serious and deadly consequences. These campaigns are able to build upon the climate of mistrust and fear that traditional and social media, perhaps unwittingly, help to reinforce. There are real and potentially harmful repercussions when people lose trust in an institution, individuals or groups in society, and Ms. Wanless suggested some strategies those in the audience could use for combatting propaganda:

- Update CPRS’s digital codes of ethics

- “Just because we can, doesn’t mean we should” a reference to the influence strategic communicators yield and “doing the right thing” at all times

- Go with trust: act honourably and transparently

- Think before you share. If a social media post provokes a response in you, figure out why. What is the source of the post? Is it political? Resist the urge to share every tweet, Facebook post and YouTube video that angers, upsets, frightens or frustrates you. Are you contributing to the problem by sharing fake news?

Result from the 2019 CanTrust Index, shared at CPRS’ annual conference, June 2019. In 2019, trust has dropped to 39%.

Why should any of this matter to scientists? Well, the CPRS conference also featured a presentation by Bruce MacLellan, CEO of Proof, on results of the firm’s 2019 annual Trust Index. In Canada overall trust is declining, although here and elsewhere trust remains high for scientists.

“Today, about 7 in 10 people say they trust scientists, although more than half the world’s population admits it understands little about science.” Reported in U.S. News, these findings come from a survey of 140,000 people who participated in a survey recently published by Gallup and the Wellcome Trust.

The public has a tendency to believe scientists, giving them an advantage in combatting propaganda and misinformation, but they may need to employ some of the tactics, such as testimonials and anecdotes, used by the “anti” and “denier” camps, to be successful.

As Dr. Samantha Yammine wrote about in “Warming up to better public relations for scientists,” scientific consensus and public opinion are not aligned on the topics of stem cells (access to unapproved therapies), genetically modified organisms, vaccines and climate change. She writes: “Given that people consider more than data alone when making decisions, to encourage evidence-based behaviours and decision-making by simply sharing information is not likely to be effective on its own: we, as scientists, must also exhibit warmth to be effective communicators.”

Forgive this generalization, but scientists tend to speak in “black and white” and they avoid murky gray areas. They like to be absolutely certain when speaking to media, for example, which is why they rely so heavily on data to support their arguments or point of view. “Others” want to sway their audience, to be persuasive and impactful, and don’t always feel compelled to deal exclusively in the truth. That makes for an unbalanced playing field and one that leans in their favour.

A 2017 article in Nature for the Humanities and Social Sciences states that science communicators (and presumably scientists) are socialized into communicating information in a way that “emphasizes the repetition of emotionless objectively sterile information,” but this isn’t very persuasive when people are making decisions or processing information. The authors suggest that to connect with audiences “communicators would do well to recognize themselves as storytellers – not to distort the truth, but to help people connect with problems and issues on a more human level….”

Watch Claire Wardle, a Research Fellow at Harvard University, discuss fake news and understanding the disinformation ecosystem. I encourage you to stick around to the end where she proposes solutions.

Stacey Johnson

Latest posts by Stacey Johnson (see all)

- Right Turn: Top 10 blogs from 2025 - January 9, 2026

- Right Turn: Season’s greetings and upcoming event - December 25, 2025

- Right Turn: Stem cell supplements: A growing market with growing risks - December 19, 2025

Comments