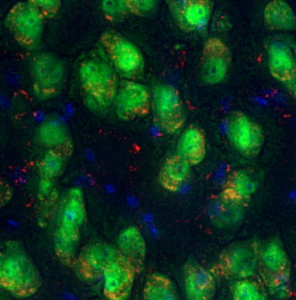

Six-month correction of lysosomal storage disease (lysosomes are in red) using stem cell gene therapy with lentiviral IDS fused to ApoEII in neurons (green) in the brain of the MPSII (Hunter syndrome) mouse model. (Nuclei in blue). Image provided by Prof. Brian Bigger, University of Edinburgh.

Hunter syndrome is one of the mucopolysaccharidoses, a group of lysosomal storage disorders caused by specific genetic mutations and missing enzymes. In Hunter syndrome, mutations in the X-linked iduronate-2-sulfatase (IDS) lead to deficiencies in the IDS enzyme, causing the accumulation of heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate within cells. The build-up of these sugars drives neurodegeneration, which leads to speech problems and dementia, as well as skeletal abnormalities and cardiorespiratory disease. It affects mostly males due to its X-linked inheritance.

Enzyme replacement therapy (ERT), introduced in the 1960s, is currently the only approved treatment on the market for Hunter syndrome and other lysosomal storage disorders. However, ERT has major limitations.

In an interview with me, Prof. Brian Bigger, from the University of Edinburgh, explained that “Enzyme replacement therapy works really well for many lysosomal storage disorders – as long as you’re trying to target parts of the body that are reachable by the bloodstream.” For example, bones and joints are hard to reach by the bloodstream and therefore have minimal access to the enzyme. The enzyme itself doesn’t reach the brain either due to the blood-brain barrier, which is an endothelial cell layer that excludes any large protein from the brain, preventing the therapeutic enzyme from crossing into the brain to remove toxic build-up of molecules in the neurons.

Another downside to ERT is that it must be administered for life, at a hospital, by intravenous infusion. Infusions are done weekly, each lasting 2-4 hours – a regimen that is burdensome for patients and families. It is also costly to produce and prepare, and is therefore very expensive to administer. Idursulfase, brand name Elaprase, the ERT drug that breaks down heparan sulfate and dermatan sulfate, is the widely approved standard of treatment, but it has an annual drug cost of over CA$650,000 for a patient weighing 77 pounds.

In recognition of these limitations, Prof. Bigger and his team developed a hematopoietic stem cell (HSC) gene therapy for Hunter syndrome, now in Phase I/II clinical trials.

The clinical team, led by Dr. Simon Jones and Dr. Rob Wynn, administers G-CSF and Plerixafor to mobilize the patient’s stem cells from the bone marrow into the bloodstream, allowing the team to collect the patient’s original HSCs.

The collected HSCs are modified (transduced) using a lentiviral vector. The lentiviral vector allows for the incorporation of the correct IDS gene into the patient’s HSCs, replacing the defective gene. After quality control assessments to check for HSC viability, sterility, purity and transduction success, the patient is given Busulfan, a chemotherapy drug, to kill bone marrow cells and create space for the new, modified HSCs to engraft. Busulfan is the same chemotherapeutic used prior to a bone marrow transplant to treat someone with leukemia.

These modified HSCs, with the corrected enzyme, are returned to the patient. Once engrafted, blood cells, called monocytes, derived from these HSCs, produce and release the enzyme into the body.

However, IDS still cannot cross the blood-brain barrier (BBB) on its own.

So how do they get to the brain?

After engraftment, the modified healthy HSCs produce monocytes, which can cross the BBB. Once in the brain, the monocytes take on the same function as microglial cells and release IDS directly into the brain. Prof. Bigger notes that the correct term for these newly engrafted HSC-derived microglial cells is “peripheral-derived macrophages that are microglial-like.” Essentially, “They’re there to help clean up the brain and to act as a sort of a functional immune system within the brain,” he goes on to say.

In addition, Prof. Bigger’s team decided to construct the IDS enzyme such that it is fused to a protein tag called APOEII. This APOEII tag allows for the IDS enzyme circulating in the peripheral bloodstream to cross the BBB via receptor-mediated transport.

This dual strategy increases IDS levels in the brain far beyond what untagged gene therapy can achieve, enhancing cognitive and behavioural outcomes in the trial patients.

Prof. Bigger further explains:

“A patient who receives this stem cell gene therapy [without the APOEII attached to the IDS] will have around 20 to 200 times the normal level of enzyme in their blood circulation and only roughly one times normal enzyme levels in the brain. You’ve got a huge number of cells in your blood circulation producing enzymes for you. Which is great. But in the brain, you’ve only got the microglial cells that are producing it, and that’s why there’s so much less. So what we’re trying to do really is to drive that enzyme from the peripheral [circulation], where it’s in big excess, into the brain.”

Can you have too much of a good thing?

Pre-clinical studies show that the overexpression of IDS is not toxic. One of the reasons for this is because the IDS enzyme is only active in the acidic environment of the lysosome, which has a pH of 5. “It [higher than normal levels of the enzyme] is not going to cause a big wave of substrate degradation in the bloodstream outside of cells (the bloodstream has a pH of about 7). It all has to happen in the lysosome,” says Prof. Bigger. In addition, IDS gene expression is limited to macrophages, microglial and monocyte cells – the cells they really want to see in the brain.

However, Prof. Bigger notes that, “Too much of anything is potentially bad for you […]. So we are absolutely evaluating the effects in patients. The first patient treated, Ollie, he looks great. And he has really high levels of enzyme expression. […] I think if we were going to see any significant issues, we would have seen them by now. But, you know, it’s a trial, so we don’t know.”

The future for adults with Hunter Syndrome

If the current trial shows positive results across all five participants, who are all under two years of age, the team hopes to expand access to older patients. The challenge is that older patients who haven’t started a brain-targeted treatment early in life have already suffered from brain degeneration, and regenerating the lost neurons cannot be done by HSC gene therapy alone.

Prof. Bigger’s team is already trying to solve that problem, too. He announced at the WORLDSymposium on Lysosomal Diseases in 2023 that his team in Edinburgh is developing an induced pluripotent stem cell-derived neural stem cell therapy with the goal of replacing neurons and rescuing lost brain function. These neural stem cells will also be engineered to overexpress the healthy gene that is missing. So far, the studies are pre-clinical, but the research team is hoping to publish their results shortly.

Comments