I can recall the first time that I heard about the idea of gene therapy. It was over 20 years ago, and possibly like many students in school, I was assigned to write an essay on the ethical considerations for allowing or disallowing gene editing on humans. I remember that much of my essay focused on the ethical implications of editing superficial characteristics, such as eye colour, rather than appreciating the amount of lives that could be improved by fixing a gene causing a disease. Twenty years later, I appreciate the foundation laid by scientists, as we are starting to see an explosion of gene therapies that are improving the quality of life of patient’s across the globe.

An overview of gene therapy

Gene therapies are a unique approach to treating diseases, as they fundamentally remove or circumvent the cause of a disease, rather than managing the symptoms of a disease. Broadly, gene therapies are designed to supply a missing gene or to bypass the functions of a missing gene. While the idea of gene therapy has existed for many decades, the treatments that put this idea into clinical practice have been primarily approved in the last five years. For example, Luxturna (Sparks Therapeutics) was approved by Health Canada to treat Leber’s congenital amaurosis 2 in 2020, Zolgensma (Novartis) was approved to treat spinal muscular atrophy in 2020, and Hemgenix (CSH Behring) for hemophilia B in 2023. Other gene therapies approved in the USA, but not yet approved for clinical use in Canada, include, Roctavian (BioMarin Pharmaceuticals) for hemophilia A, Vyjuvek (Krystal Biotech) for epidermolysis bullosa dystrophica, Elevidys (Sarepta Therapeutics) for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. If you include cell therapies, there are even more therapies that use the principles of gene editting, such as CAR T. Most recently, Casgevy (Vertex Pharmaceuticals) was approved for the treatment of sickle cell disease in both the UK and USA.

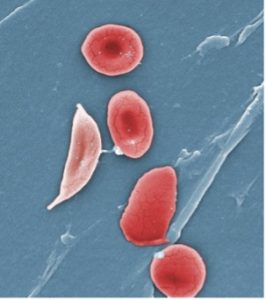

Electron microscope image of a sickled red blood cell (left) next to normal red blood cells (right). Source: https://phil.cdc.gov/

CRISPR-based gene therapy of Casgevy makes this intervention unique

Casgevy plants the flag for the first CRISPR-based therapy, approved for use in humans in the UK and USA. For those unfamiliar, the CRISPR/Cas9 system is the Nobel prize-winning discovery of 2020 that allows for precise changes in a cell’s DNA. Statsnews has a video demonstrating how this technology works. In short, the primary advantage of CRISPR/Cas9 systems is their precision for introducing genes into the genome, mitigating off-target effects.

It is not the only gene therapy approved for sickle cell disease, as Lyfgenia (Bluebird Bio) is another lentiviral-based gene therapy also approved by the FDA for the treatment of this disease. However, Casgevy has been gaining more headlines for three primary reasons: 1) unlike Lyfgenia, Casgevy does not have a boxed warning from the FDA indicating blood cancers have arisen in treated patients; 2) Casgevy is US$900,000 cheaper than Lyfgenia; and 3) Casgevy is the first in-human therapy using CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing techniques.

How does Casgevy work?

Casgevy is one-part gene therapy and one-part autologous cell therapy, as it involves the removal and processing of bone marrow stem cells from a patient donor, followed by their re-introduction back into the same donor. These bone marrow cells are modified to disrupt the BCL11A gene so that fetal hemoglobin is produced by the patients. As long as the levels of fetal hemoglobin remain high, the risk of damage from red blood cell sickling is low.

How could Casgevy improve health care?

Agencies covering the costs of gene therapy always consider whether a new therapy improves upon existing medication. So, the burning question is: what does Casgevy improve upon?

In recent news headlines, there has not been much reporting of an existing comparable and widely-used “one time” cure for sickle cell disease: bone marrow transplants. Fundamentally, the mechanism of action for Casgevy and bone marrow transplants are similar. For example, Casgevy and bone marrow transplants both require chemotherapy drugs to eliminate the patient’s functionally impaired bone marrow stem cells, and replace them with functioning cells. The primary difference is that Casgevy uses gene editing and an autologous cell therapy approach, while bone marrow transplants take an unedited, allogeneic (cells from a donor) approach. So, how does this make Casgevy superior to bone marrow transplants? Since Casgevy uses a patient’s own cells, it circumvents the need to find a suitable donor match for a bone marrow transplant. Effectively, this greatly improves health care equity, as ethnic background is a major factor contributing to the success of finding a matching donor.

We need to talk about the costs, as these life-changing gene therapies may only increase health care disparities across the globe

Image of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing, showing the replacement of a gene in a DNA strand. Image provided by the National Human Genome Research Institute (https://www.genome.gov)

Gene therapies are expensive, and Casgevy is no exception with its estimated cost of US$2.2 million. As more of these expensive therapies get approved, there are discussions around how health-care systems across the globe are going to support patients that would benefit from these treatments. For example, funding models in high-income countries were not created with these costly “one time” treatments in mind, and there is speculation that insurance agencies will soon restrict their coverage of gene therapies, despite the fact that these price tags are cheaper than a lifetime treatment of other disease-modifying drugs.

Meanwhile, these prices put these treatments out of reach for middle- and low-income countries. This latter fact is important to mention, especially in the context of sickle cell disease, as this disease is most prevalent in sub-Saharan Africa, with around three quarters of patients with sickle cell disease living in this geographical area. In comparison, high-income countries account for roughly 2 per cent of all global sickle cell disease cases. These discoveries will likely do nothing to improve the quality of life in these communities, despite there being enormous opportunities to improve patient health.

Cost, however, is just one barrier to bringing these treatments to sub-Saharan Africa. The medical infrastructure to create these autologous cell therapies is another critical factor that would need to be developed. In the immediate short term, it may be more viable to increase access of hydroxyurea in these areas.

It is an exciting time to be in the regenerative medicine field, as the decades of research are finally seeing tangible outcomes and producing revolutionary treatments. What was once considered science fiction has moved into the realm of reality, but we need to remember not to leave too many patients behind. I am not sure of the most ethical way forward, but I know the industry is having discussions about patient access. As one suggestion, perhaps a small portion of profits could be used to offset other drugs for less wealthy countries.

Whatever we decide to do, humans must put effort into achieving health care equality for everyone. Otherwise, as my childhood friend put it, we may become a reflection of Lex Luthor in the 2007 movie Superman: Doosmday.

Tyler Wenzel

Latest posts by Tyler Wenzel (see all)

- Promoting cell and gene therapies versus the risks of “scienceploitation” - January 16, 2025

- Casgevy, a world-first CRISPR-based gene therapy, aims to cure sickle cell anemia - December 21, 2023

- Overcoming the limitations of allogeneic transplants to treat incurable diseases, TMM2023 - November 23, 2023

Comments