Canada is home to some of the world’s top stem cell scientists: we’ve led the discoveries of stem cells in the brain, retina, blood, skin and several types of cancer stem cells, and continue to push science’s understanding of these promising cells each year.

But there’s a dark side associated with all the hope surrounding stem cells as the treatment for so many diseases and conditions. Many private companies continue to co-opt these scientific discoveries and the language describing them to sell unproven and sometimes dangerous “stem cell” procedures. A recent study from Leigh Turner found 30 companies running 43 such clinics across six provinces in Canada, more than half of which are in Ontario.

These unapproved treatments not only pose a direct threat to patients, but they can also take patients away from legitimate clinical trials, thus threatening the academic research enterprise at large. Plus any publicly reported adverse events could hinder progress for legitimate clinical trials as was seen in the past with gene therapy trials. Despite multiple warnings from various groups, patients continue to frequent these clinics and seek treatments.

Trust in science and scientists

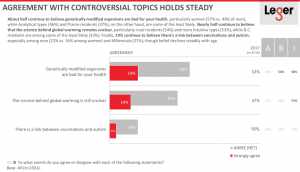

Stem cells are not the only topic where scientific consensus and public opinion are not aligned: a survey from the Ontario Science Centre (OSC), earlier this year, showed many Canadians hold scientifically unsupported views about GMOs, vaccines, and climate change.

Image from the 2018 Ontario Science Centre Science Literacy Survey

It might be tempting to react to these ideas by organizing awareness events where scientists tell the public about our latest research. While this is important for a variety of reasons, raising awareness and sharing information alone may not be the most effective approach for changing attitudes.

First, in that same OSC survey, Canadians self-report varying levels of analytical vs. intuitive approaches to making decisions, with a higher proportion of intuitive thinkers agreeing with claims that are inconsistent with the scientific literature (see ABI scores in the figure above, where A = analytical, B = balanced, and I = intuitive values for decision-making).

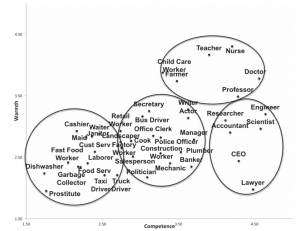

Second, seminal research by Susan Fiske suggests warmth and competence are two fundamental dimensions used to determine interpersonal and intergroup behaviours. Her research shows that scientists were rated high on competence, but relatively low on warmth, according to a more recent study.

Figure 2: Fiske & Dupree, 2014

And third, public trust in scientists has remained stable for the last four decades, at least according to American data collected by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago. Recent data from an international survey conducted by 3M and the OSC Science Literacy Survey report even higher values for trust in scientists in our society. Trust levels are stable, but there is a persistent population that is skeptical of science, which suggests it is time for a new approach if we want to see different outcomes.

Given that people consider more than data alone when making decisions, to encourage evidence-based behaviours and decision-making by simply sharing information is not likely to be effective on its own: we, as scientists, must also exhibit warmth to be effective communicators.

Upping our game

While we are trained to only consider data and remove rhetoric (persuasive language) from our presentations, we should not be so quick to apply these same techniques to our public communication strategy (so long as we always promote evidence-based information and do not compromise accuracy). After all, the people “on the other side” are certainly using testimonials, anecdotes and more to sell their unapproved products and make their unproven arguments.

But cultivating warmth is not an easy thing to do, particularly when only 43 percent of Canadians report personally knowing someone in a science-related job. So how do we get our warm and informative messages out to everyone, despite barriers in geography and limited resources?

My answer is to mimic the approach taken by those promoting pseudoscience: use social media. There are many stem cell clinics employing direct to consumer marketing to reach patients. If you’ve seen people selling supplements out of context with little concrete evidence for doing so, “skinny teas” and hair gummies…you know what I mean. There’s no reason why truthful and accurate information cannot be a part of these widespread online conversations.

The high volume of people on these platforms (Instagram recently reported 1 billion monthly active users!), our need for better public relations, and the ability to humanize information through visual and honest storytelling make social media the ideal platform for high-throughput, but reader-friendly, forms of science communication.

While my communication method of choice is social media, it is only one approach to changing our image and conveying more warmth in our science communication and different approaches should be encouraged. No matter what you choose, there is ample research on science communication strategies to consult so that all efforts are effective and ethical.

This does not mean every scientist needs to become a science communicator. However, scientists who are interested in science communication should have their efforts supported by training programs, and valued in hiring and funding decisions. For those not interested in doing this, research grants or professional societies could include budgets to hire professional communicators. Given that our research funding comes from public tax dollars, effective engagement strategies are imperative to showcase a return on investment to taxpayers and foster a positive science culture in future voting populations. Fortunately, these efforts could fall under knowledge translation, which is encouraged in our work.

Search #ScientistsWhoSelfie and #scicomm on your favourite social media platform to support and/or join grassroots efforts to bolster warmth through digital science communication! You can read more about these concepts in this interview with social psychologist Dr. Susan Fiske by Science Writer & Researcher Dr. Paige Jarreau, both of whom inspired and educated the author for this piece.”

Latest posts by Samantha Yammine (see all)

- Communicating new science in a crisis - April 2, 2020

- Warming up to better public relations for scientists - November 22, 2018

- Bioprinting tissues of the future with Dr. Stephanie Willerth - November 16, 2018

Comments